Two Short Notes: Bower & the deity from Yarkhoto.

Reflections on H literature of Kucha through the Bower Manuscript and inspecting the mysterious deity from Yarkhoto.

Short Note#1: H Traditions of Central Asia as noticed through the Bower Manuscripts.

In the year 1890, Lieutenant H. Bower and his team were camped in Kucha in pursuit of the murderer of one Scotsman Dalgleisli at the behest of the British Government in India. Kucha, or Kuchar in the local tongue is one of the principal oases located on the peripheries of the Tian Shan mountain range and the Takla Makan desert. Here, Lt. Bower was sold these manuscripts by a local man, which he then took to Shimla in the same year. Here, the manuscripts were submitted to Colonel J. Waterhouse, the president of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and exhibited in a meeting on November 5th, 1890. For a long while, the manuscripts remained undeciphered although it was generally understood that they were very ancient and also helped provide stimuli for a series of cultural and archaeological campaigns in oases cities.

The mystery surrounding the manuscripts came to an end between 1893-97 when it was deciphered to be Saṁskr̥ta written in Early-Gupta Brāhmi by Rudolf Hoernlé, who published a series of comparative notes and translations on it. The manuscript consists of seven parts and three distinct writing styles can be observed based on its palaeographic analysis. Parts I-III style belongs to a northern Indian scribe under the influence of the Śāradā and Kuchari script; the style of Part IV suggests a native Chinese scribe who was used to writing with a brush; while that of Parts V-VII show southern Brāhmi influence as witnessed by the position of dots in vowel ‘i’. The manuscripts are notable for preserving the original ancient Indian numeral notation system that employed twenty signs. Nine were for the units, nine for the tens, one for hundred, and one for thousand. Out of these twenty, we find thirteen occurring in our manuscripts given below. The sign for fifty here is unlikely to be correct, however, a layman might notice some conservativeness in the characters for 2, 3, 4-5:

We also find distinct signs which are equivalent to the modern comma and semi-colon; for correction or indicating absence; or for indicating that a given gloss is an extract from a previously existing authority. Paleographic analysis and study of epigraphic and literary sources point to the fact that the bulk of the manuscripts fall within the range 350-375 AD while some segments in later parts would fall between 470-530 AD. Parts I-III are treatises on medicine while parts IV-VII are treatises on divination and magic. The former parts follow scholastic Sanskrit while those in the latter parts have plenty of Prākr̥ta words and also grammatical errors. The former parts constituting the three medicinal treatises are entirely metrical in composition. Anuṣṭubh dominates the composition with 933 out of 1323 verses, which is 70% of the whole, followed by Triṣṭubh accounting for 121 verses and Āryā for 109. The later parts [IV-VII] are written entirely in prose and their scribes do not appear to be well-versed in scholastic Sanskrit.

Part I of the manuscript is a medicinal work of original character written by an Astika undoubtedly on the character of Garlic. It opens up with a beautiful description of a Himalayan setting and praises Bhagavān Śiva:

Om ! The holy summit of boundless wealth, inhabited by companies of Devarshis and Siddhas, by Kinnaras, Nagas, Yakshas and Vidyadharas, delightful with clouds towering up to the firmament of heaven, all...........overtopping — [1]

Where, scattered in every direction by reason of the multitude of the rays of thousands of protruding gems, and dissolved by fear, darkness, being apprehensive of the abode of the moon, stars, sun and fire, does not venture to approach even in the nights of the rainy season — [2]

Which is incessantly worshipped by numerous companies of sages accompanied by tlioir disciples, carrying wood, ku^a-grass, fruits, water and flowers ; in wiiose groves the trees have their branches searched by the celestial maidens in quest of flowers — [3]

Where, under the touch of the rays of the lord of the stars (i . e the moon), who permanently rests in one place of the crest of matted hair of the Three-eyed-one [Śiva], the precious moon-stones, even by day, let flow a copious stream of water, cool and clear, like the crystal of the Himalayas — [4]

In whose beautiful groves, crowded with trees bearing flowers and fruit, resounding with the voices of swarms of various kinds of birds, and. having their roekv ground washed by the water emitted by the clouds, the medicinal plants glow at night like sacrificial fires — [5]

This heavenly adobe where medicinal plants glow at night like sacrificial fires is described to be the dwelling of many Seers, who would inquire into the forms, names and properties of said plants:

On that mountain, which is, as it were, the dream of the whole earth and, through its gifts of the riches of the world, the benefactor of all creatures— on its summit, delightful with its trees bearing flowers and fruit at all seasons, there dwell the following Munis of enlightened mind: —[8]

Ātreya, Hārita, Parāśara, Bheḍa, Garga, Śāmbavya, Suśruta, Vasiṣṭha, Karāla apd Kāpya. Hundreds of times they used to roam about, in company of one another, enquiring into the tastes, properties, forms, powers and names of all medicinal plants — [9]

From among the mentioned Seers, Ātreya is quoted extensively in Part II, one medieval work titled Vaṅgasena confessing to being the recast of the Ātreya Saṃhitā is also known to us. We are also aware of one Hārita Saṃhitā and Hārita is said to have learnt medicine from the adobe of Ātreya in the Himalayas. Bheḍa is extensively quoted in Part II as well and we are aware of one Bheḍa Saṃhitā too. Finally, Suśruta is all too well-known as the celebrated author of Suśruta Saṃhitā and we are lacking in knowledge of the rest. The work resumes with an ancient tale in which Suśruta approaches Muni Kāśirāja, who is likely to be Dhanvantri, to enquire about the origins of the garlic:

Having observed a plant with leaves dark-blue like sapphire, and with bulbs white like jasmine, crystal, the white lotus, moon-rays, conch-shell or mica, and having his attention aroused thereby, Suśruta approached the Muni Kāśirāja with the enquiry, what it could be. Then that holy man replied to him as follows : —[10]

Of yore the lord of the Asuras himself drank the forth-churned nectar; his head the holy Janārdana [Viṣṇu] cut of. The pharynx remained attached to the severed head ; from it drops fell on the ground, and those were its [garlic’s] first origin. —[11]

Hence Brāhmaṇa-s do not eat it, because of its having originated from something connected with a living body; its evil smell also the learned in sacred lore declare to be due to the same cause. — [12]

Suśruta is presented with a mythical account relating it with Viṣṇu’s slaughter of the Asura-s after the latter drank nectar churned out of the oceans, and we learn of the mythical account of why Brāhmaṇa-s avoided garlic. From the Spitzer manuscripts, we learn that Śaka also avoided garlic. One can wonder to what extent did such accounts influence them. The rest of the treatise constitutes of various irregularly arranged treatments employing garlic: commencing with the regulation of digestion; preparation of aphrodisiacs; formulae for eye lotions; preparation of face-plasters; remedies for hair fall; remedies for cough and cold etc.

Part II goes by the name Navanītaka and opens with a single-line salutation to Śakyamuni, indicating the Nastika leanings of its scribe. Unlike Part I and Part III, it is not an original work but a compilation which professes to give the reader the best practices available from medicinal treatises of those times. A minute small fraction of them also appear to added by the author himself or was borrowed from folk medicinal traditions. The work has heavy parallels with the Saṃhitā-s of Bheḍa, Suśruta and Caraka. It also cites a number of archaic medicinal traditions, as witnessed in the Arthaśāstra with political traditions, these are:

Kaṅkāyana [935]

Nimi [883-7]

Suprabha [633-7]

Uśanas [846-7]

Vāḍvali [319-24]

Br̥haspati [784]

Agastya, [588-9 & 905-9]

Dhanvantari [232-40 & 968-76]

Jivaka [1081 & 1097]

Kaśyapa [1011-1040]

Ātreya. The head of the medicinal tradition at Takśaśila [multiple verses]

Aśvin deities.

Br̥haspati & Uśanas were certainly historical schools flourishing in 4th-century BC. Dhanvantri is the divine founder of surgery. Nimi again is an archaic semi-mythical king of Videha who is credited with the founding of ophthalmic sciences. Jivaka appears to be the physician at King Ajātaśatru’s court and Kaśyapa appears to be a historical figure as well. Vāḍvali is an archaic patronym mentioned by Pāṇini and then only by one unknown medieval Cālukya physician. The technical aspects of the work are too broad to be covered, instead, we’d like to share two simple examples with us here — indicating again that even though the compiler was a Nāstika, all Āstika elements remained in the treatise:

In the winter one should regularly eat Aśvagandhā and black-sesamum seeds, raised with sugar; and after it milk should invariably be drunk. This treatment has been appointed by God himself as a means for imparting to any one the strength of Viṣṇu; by observing it for twelve days even an old man will become young. — [782]

Dhanvantari, the most wise, was asked by Keśava [Viṣṇu]: Is there any medicine at all capable of curing all diseases ?

Hearing the query of Keśava [Viṣṇu], Dhanvantari replied: Comparable with the plumbago-plant there is no medicine: so it is said. Know also that it is of three kinds: black, white, and yellow, respectively distinguished as the best, the least, and the middling. To patients suffering from skin-diseases, morbid secretion of urine, enlargements of the abdomen, and white leprosy, mark that the black variety is particularly beneficial. — [969-971]

One should also notice the following verse: in a manner, these medicinal treatises were the backbone of the spread of Aryan culture. We noted the popularity of Brāhmaṇa medicinal treatises in the Sinosphere in our previous post here. Indeed, they were readily assimilated by Nastika-s which enabled them to gain significant converts, as was part of their strategy as discussed in this Twitter thread.

Having offered a prayer to the Deva-s, and invoked the blessing of Brāhmaṇa-s, as is proper, and in a place where there is no cemetery, nor barren saline soil, nor anthill, nor caitya …

Part III of the manuscript is a short medicinal work existing only in fragments and some material consistent with Part II, the bulk of the manuscript was destroyed over the years probably, leaving us with only four leaves. Parts IV-V are two independent Āstika works of Pāśaka-Kevali, that is Cubomancy — the art of divination by throwing dice. An elongated cuboidal die was cast three times and the number sequence was used to perform divinations. A die would have one, two, three or four pips on it and a total of 64 combinations were possible. The manual in Part IV contains 60 out of the 64 combinations while the manual in Part V contains a mere 20.

The Vaiśnava character of the Cubomancy manual in Part IV is hard to miss. The leaves open with a salutation to many Āstika deities and in particular to Viṣṇu, who is regarded as the tutelary god of divination. Since we do not have parallels from India regarding this work — it can be deemed original and thus seen as an insight into Āstika traditions in Central Asian Oases:

नमो नन्दिरुद्रेश्वराय नमो आचार्येभ्यः नमो ईश्वराय नमो माणिभद्राय नमस् सर्वयक्षेभ्यः नमः सर्वदेवेभ्यः शिवाय नमः षष्टीये नमः प्रजापतये नमः रुद्राय नमः नमो वैश्रवणाय नमो मरुतानां नमः

Salutation to Nandirudreśvara ! Salutation to the Ācārya-s ! Salutation to Īśvara ! Salutation to Manibhadra ! Salutation to all Yaksha-s Salutation to allDeva-s. To Siva salutation ! To Shashthi salutation ! To Prajapati salutation ! To Rudra salutation ! Salutation to Vaiśravana ! Salutation to the Marutas ! Salutation !

प्रासका पतन्तु इमस्यार्थस्य कारणा हिलि कुम्भकारिमातंगयुक्ता पतन्तु यत् सत्यं सर्वसिद्धानां यत् सत्यं सर्ववादीनां तेन सत्येन सत्यसमयेन नष्टं विनष्टं क्षेमाक्षेमं लाभालाभं जयाजयं शिवानुदर्शनस्य स्वाहा सत्यनारायणे चैव देवते ऋषीषु चैव सत्यं मन्त्रं वृत्तिस् सत्यं समक्षा पतन्तु स्वाहा सत्यं चैव तु द्रष्टव्यं नि x x x x x x x x x x मन्त्रौषधं च निमित्तबलम् अन्तरं मृषतायां देवतं विष्णु नविकायां चण्टयाण्ट

Let the dice fall for the purpose of the present object (i.e., of soothsaying) ! Hili Hili ! Let them fall as befits the skill of Kumbhakāri, the Mātaṅga woman! By the truth of all the Siddhas, by the truth of all Schools, by their truth and true consensus let Siva declare what is lost and preserved,peace and trouble, gain and loss, victory and defeat, svaha ! On the holy Narayana, the tutelary Devata, and on the Rishis rests the truth of the oracle, the truth of the process of divination. Let the dice fall openly ! svaha I Let the truth be seen ! The efficacy of magical formulas and medical herbs and prognostics..................... is far from untruth. In praise of the Devata Vishnu.

The mention of the Mātaga woman probably relates to their proficiency in magical arts, as witnessed in an episode of the Divyavadana. The use of the term Hili is a Prakriticism borrowed from a mleccha tongue, something noted by multiple H seers, who also cautioned against its use: [credits to @Satoverma on Twitter]

Upon the casting of a die thrice, the sequence could then be read from the manual and fortune be predicted. To give a few examples:

444: Salutation ! Janārdana is well-pleased with thee who art an excellent man. All thy enemies are killed. What thou shalt desire, that shall be done.

434 : I see a terrible effort against those with whom thou hast a conflict, but I see the work to be fruitless on account of which thou enquirest.

134 : Thou art planning a meeting, and that will soon come to pass; the order has gone forth from the Aśvin-s, nor will it be anything unpleasant.

442: Whatever there is in thy house, cattle, grain and money, thou shouldst distribute among the Brāhmaṇa-s ; thy advancement is then near at hand.

233 : I see thy purpose ; it is with reference to some biped ; it will come to pass for thee as surely as the word of Māruta.

331: The safety of thy person, profit and wealth are within thy grasp, and thy prosperity is at hand as sure as the word of Māruta.

212 : Animal sacrifices and many other sacrifices thou wilt sacrifice ; and complete oblations thou wilt give : there is no doubt about it.

133 : Thou speakest the untruth sometimes, and thou showest always ill-will to thy friends ; but wait, and by the favour of the devatas, thy prosperity will come to pass.

The practice mentioned in passing depicts a situation of Āstika-s in Central Asia to be similar to that in India. We notice this in the prescription of Devata worship for good luck; conducting Yajña-s; invocation of Aśvin-s, Māruta and Viṣṇu; and doing charity to Brāhmaṇa-s. Hoernlé notes the similarity between the Tibetan and Mongol wind horses and the invocations of Māruta, the wind god, as the bringer of good luck.

Part V of the manuscript is yet another divination manual and we find it to be in conjunction with two recensions found in India, whose authorship is attributed to the Seer Garga. The recensions found in India speak of Cubomancers possessing Horajñāna [Greek: ὤρα] — which has been traced to be the Lunar Mansion doctrine of the Roman astrologer Julius Firmicus Maternus from 335-350 AD. This transmission was in line with a number of scientific exchanges between India and the Greco-Roman world, like the adoption of ‘Aux’ in the West from Skt. Ucca → the apex of the orbit of a planet. The philosopher Porphyry of Tyre writing about 260 AD informs us that a number of Indians would visit Alexandria, from which such exchanges of information could take place. Also notable are the Saṁskr̥ta transliterations of Greek zodiac signs in Varāhamihira’s treatise:

Thus, the recensions present in India are unlikely to be earlier than the fifth century. The manual available in Part V of the manuscripts have no such reservation and thus can be deemed to be belonging to considerable antiquity. Its introduction too is different from the recessions available in India [A-F & G] and can be considered original writing:

Note that the first verse is missing in the Bower Manuscript and has two distinct versions in the Indian recensions. The second verse is common in the Indian recensions and distinct in the Bower one. The third verse is also common to the Indian recensions but distinct in the Bower recension. Notably, it is a salutation to Devi in all cases. Indian scribes when copying a text would often add an introduction, index or salutation at the beginning or the end. Thus, we posit that the original recension, written by Garga, began with a salutation to Devi, which is the 3rd verse present in current recensions. At a later stage around the second century, it branched into two where two independent scribes copying it added the 2nd verse. One of these is the father of the Indian recensions, which branched again at a later stage as noticed in the 1st verse, while the other is the Bower manuscript. Depending on when this branching may have occurred, we may see it as reflecting the views of the patron. It opens up with a salutation to Viṣṇu just like in Part IV, followed by a prose for the Devi:

महादेवं नमस्यामि लोकनाथं जनार्दनं येन सत्यम् इदं दृष्टं य दिव्य [1] xxxxxxxxxxxx प्राहु तत् सद्भि ह दृश्या [2] ताला भाला का सुखं दुःखं जीवितं मरणं तथा इह सर्वं मनुष्याणां मरुद्भि समुदीरितम् [3] रिषिभि निर्मिता xxx मेरुवासं प्रयोजिता इमा विद्या ततस् तेषां हृष्टा वै मारुतादयः [4]

I salute Janardana [Viṣṇu], the lord of the world, by whom the truth of this art of divination has been decreed. What is divine XXXXXXXXXXXXXX that, being understood by good men, is declared. Signs on the palms and the forehead, good and ill fortune, life and death, in short all that may happen to men is here [in the art of divination] declared by the Maruts. Composed by Rishis, and fit to be used by those who reside on mount Meru, is this charm: hence thereby the Maruts and others are made favourable to them that use it.

तद्यथा -- विमले निर्मलो देवि देवि व x x यत् सत्यं यत् सु तं तत् सर्वं दरिशय / अपेतु मानुषं चक्षु दिव्यं चक्षु प्रवर्ततु अपेतु मानुषं श्रोत्रं दिव्यं श्रोत्रं प्रवर्ततु [१] अपेतु मानुषं गन्धं दिव्यं गन्धं प्रवर्ततु अपेतु मानुषा जिह्वा दिव्या जिह्वा प्रवर्ततु [२] मालि मालि स्वाहा

It runs as follows:— “ Oh thou pure, pure, stainless Devi! Oh Devi! That which is true, that which is well, all that do thou show to us. Though the human eye may fail, the divine eye will prevail; though the human ear may fail, the divine ear will prevail; (2) though the human smell may fail, the divine smell will prevail; though the human tongue may fail, the divine tongue will prevail. Oh thou Garlanded One, thou Garlanded One! Svaha”

The term Mālinī [The garlanded one, here Māli] is an epithet of the great goddess, the spouse of Śiva, the exact form cannot be identified. Nonetheless, we do find a tradition of worship of Devi in Central Asia as witnessed in the given two murals and a number of artefacts.

Above: Śiva and Durga sitting on the bull Nandi, flanked by a guardsman from Dilberjin.

Above: A reconstructed image of Nana-Durga from Panjikent.

Above: Śiva and Pārvati from Kizil caves.

The rest of the content of the manuscript follows the same style as Part IV, dealing with dice sequence and prediction of fortune. We will share a few examples here:

144: When one comes first and then twice four, then thou will attain progress in all thy businesses and wealth: thy family Deva, Maheśvara, the great Deva, will be favourable to thee : give praises to him and worship, and keep his vigils. Very great will be thy gain : there is no doubt about it.

414: The object which thou art thinking of, that indeed is auspicious for the promotion of thy advancement: but thou doest not respect thy father and mother, nor thy friends and relatives, nor doest thou worship the elders, nor Maheśvara Śiva, thy family Devatā. Hence none of the goods which thou thinkest of will come to thee. But if he, Śiva, is propitiated, he will give thee peace and the desire of thy heart.

141: Varied gain is indicated for thee, and thy good fortune is at hand. Continuously worship Janardana [Viṣṇu] with offerings of garlands, and always manage to be a friend to all creatures. Then thou shalt be long-lived and wealthy .

424: It indicates something uncertain and even mysterious : do not thou turn thy thoughts to it. (Thou designest acts of temerity in thy mind; but they will elude thee. Seek the protection of God !

412: Strenuous exertions are being made by thee and thy poverty is very great. Thou shalt be delivered from it; do not be anxious! This is a weightly matter that thou art thinking in thy mind. Vināyaka, the remover of obstacles will turn away thy troubles and thy poverty. Cleansed from sin and prosperous, thou shalt obtain everything.

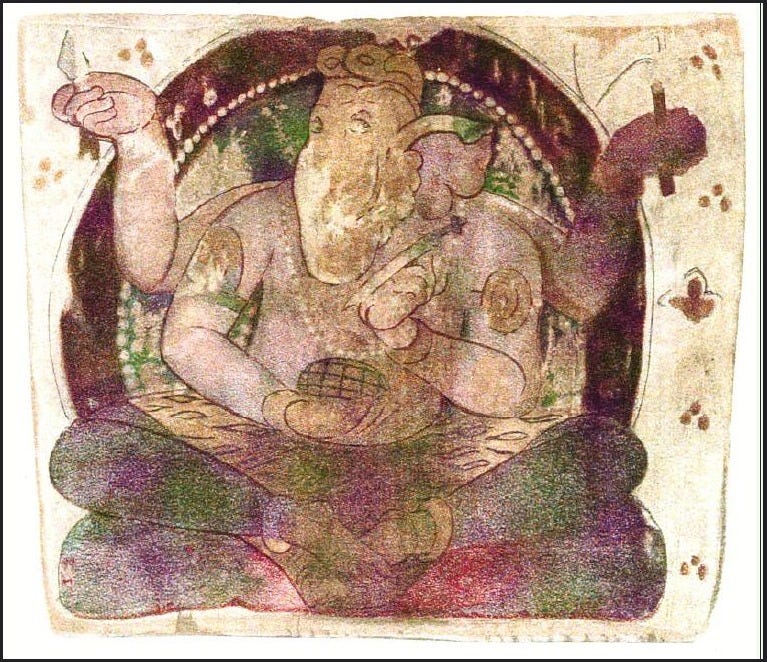

Once again, the recommendations all stress worshipping Kuladevatā-s, Śiva, Viṣṇu, Devi and Vināyaka for good fortune and turning away troubles and poverty — imparting us with more knowledge about Arya traditions in the oases. The mention of Vināyaka in the Astika context is rarer, however, there was indeed a tradition of his worship as witnessed in this plaster here from Khotan:

There was also this fragment of a Manichaen manuscript depicting him: On the left is Gaṇeśa; then is Viṣṇu in his Varāhāvatara [quite popular a form in imperial imagery]; then is Brahmā and finally Śiva at right.

And finally, @huntersrolinson from Twitter pointed out another Gaṇeśa image from Endere:

Parts VI and VII contain two different portions of the Nastika text Mahāmāyurī Vidyārājñī. They contain a number of Dhāraṇī charms against cobra bites and seizures respectively. The two parts contain the name Yaśomitra at the end which was likely the name of the monk or patron who commissioned the writings and built the mound where these were found. Part VII is very short and does not merit any discussion apart from the fact that it draws a distinction between Śramaṇa-s and Brāhmaṇa-s — who are described to be eternal enemies by the Śuṅga seer Patañjali. Whereas in Part VI, we see a Nastika polemic against H divinities who are named as the cause of seizures against which the protection charm is recited:

“O Blessed One, how can I effect this man’s recovery ? ” When he said this, the Blessed One spoke thus to the venerable Ananda: “ Go thou, O Ananda, and with the word of the Tathfigata save the mendicant Svāti, with that great Mayurī spell, the queen of the magic art!

Grant him safety, security, defence, salvation, protection, relief and recovery, preservation from danger, counteraction of the poison, destruction of the poison, and apply a ligature to the wound, a ligature to the vein! Deliver him from seizure by a Deva, from seizure by a Naga, from seizure by an Asura, from seizure by a Maruta, from seizure by a Garuda, from seizure by a Gandharva, from seizure by a Kinnara, from seizure by a Maharaga, from seizure by a Yaksha, from seizure by a Rakshasa, from seizure by a Preta, from seizure by a Pishacha, from seizure by a Bhuta, from seizure by a Kumbhanda, from seizure by a Putana, from seizure by a Katapdtana, from seizure by Skanda, from seizure by mania, from seizure by unnatural change in appearance, from seizure by epilepsy, from seizure by the evil eye………

……….

Marūta, Garuḍa, Skanda and Deva-s are put next to Asura-s and Rākśasa-s as the cause of seizures after a cobra bite. Indeed, the seer Patañjali’s words ring true. For a greater study of the Mahāmāyurī Vidyārājñī, we would recommend going through the Manasataramgini’s blog here.

Short Note#2: Identifying The Mysterious Deity

Recently we came across a mysterious statue from Yarkhoto, dated to the eighth century. It was originally labelled as a demon on account of its unusual appearance but more recent publications identified it as an unnamed deity since it has rather calm expressions and lacks all the ferocity of a demon. Now, as simple-minded H, we were immediately reminded of Bhagavān Kr̥ṣṇa and were disappointed to learn that it was unidentified and highly unlikely to be Kr̥ṣṇa either given the lack of traditions worshipping him in the Central Asian Oases. Nonetheless, we are determined to identify it and shall investigate some features.

Starting from the top — the hairstyle is particularly interesting, the hair is curved in a S-pattern and forms a crown around the head. We wondered if this distinct hairstyle could point us towards a particular direction and began skimming through art fragments from all over Central Asia and neighbouring regions. Out of the 1500 or more fragments scouted, we found this style on only two more stuccos. The first is shown below, we can note the distinct S-pattern hairstyle on it. It was taken from the Kizil caves and is dated to the second half of the fourth century. Four similar heads were obtained from cave#77 which Marylin Martin Rhie correctly identifies as Devatā heads. Two of them including our own bear a tilaka on the forehead giving it a more H context, however, only one possesses the S-pattern hairstyle.

What we found even more interesting was the fact that the curls have a plane of symmetry at the middle of the forehead. We also came across another stucco from Kucha which had the same S-pattern curls splitting at the middle of the forehead.

Surprisingly enough, this had a tilaka on its forehead too. Now, this is not something that we can take lightly. While tilaka-s do feature significantly, it is too big a coincidence that the two extremely rare S-style stuccos both feature a tilaka. Let us label this event as [A]. Next, we shall take a look at the X-shaped crossband the statue is wearing with the floral motif at its intersection. These X-shaped crossbands are a feature of Kushana-Gupta art which made inroads into Central Asia. They are generally present on warrior-esque figures but also on both Nastika and Astika divinities. See a few examples:

Let us label this event as [B]. These, however, aren’t the only artistic influences we see from the Gupta Era. There are two notable examples. we would like to share two examples, particularly of Śaiva art:

Let us call these Śaiva artistic influence events [C]. Finally and most importantly, there is the question of colour. The body is painted blue, which was an expensive colour produced from Lapis Lazuli fragments. In our survey, we don’t find any Nastika or Devatā imagery in the colour blue. However, we do find a bunch of Śiva images in blue. Take this Khotanese Śiva mural for starters:

Then we have a mural from Panjikent, again depicting Śiva in the colour blue:

Another mural from Panjikent depicting Sīva in the colour blue:

Finally, we have a stucco from 8th Century Sengim Agiz, which was classified as a “demon” on account of its fangs and fiery mouth. which is again blue in colour.

This, however, is indeed a misclassification. Fangs are common in wrathful Śiva images, like this piece from 9th-century Kashmir:

Or these from a more southern location:

More importantly, the third eye is a rarity and largely exclusive to Śiva, especially his wrathful forms, thus, we can indeed identify the stucco as Śiva, and blue coloured on top of that. Finally, @huntersrolinson pointed out that Śiva is variously described to have flamy hair, red hair or tawny [pingala] hair. This was indeed remarkable since both our “demon” stucco and the original statue possess red hair as well. Let this event be known as [D].

If we go by that assertion, one may feel inclined to ask why does the original figure not have a third eye, however, it is not entirely uncommon for Śiva images to lack a third eye. A number of examples can be given from both India and Central Asia as seen below.

To put things together, we witness that:

A: Our statue is possessed of the rare S-pattern hairstyle which is only seen in unidentified devatā heads with tilaka upon them. This is an extremely rare event and highly delocalized both spatially and temporally.

B: It wears the X-shaped crossbands and has garments similar to those in H images.

C: There were Śaiva influences on imagery in the Oases from India

D: Śiva images from around the Oases are seen to be blue in colour multiple times. Their blue colour is exceptional with the only other exception being that of demons, which again is an extremely rare event [I saw only two such murals out of thousands]. At times they are also red-headed.

There are images of Śiva, from both the Oases and India which do not include the third eye.

As a conjecture: we can imagine the raised hands of the mysterious deity to be holding something up above — as is common in the various four-armed Śiva images we showed here.

There are also known literary traditions of Śiva worship as witnessed in the Bower Manuscripts earlier.

Thus, putting all of these together, we can conclude with fair certainty that only Śiva could lie at the confluence of all of these paths and identify our deity as such with some localized elements.

Great Work. Tbh, before reading Note 2, my first thought on seeing the image was it looked like Shivji. Glad to see the thoroughness, must be very painstaking.

Nice article.